A Primer On Rare Earth Magnets: What does the Chinese Export Restriction means for India and its Supply Chain?

How China’s Rare Earth Export Ban is Forcing Indian Industry to Rethink Supply Chains, Accelerate Innovation, and Pursue Self-Reliance

By now, most of us are well aware of the recent headlines that have dominated both business and mainstream news: China’s decision to impose export restrictions on rare earth elements. This development has captured global attention, given the critical role rare earths play in powering everything from electric vehicles and wind turbines to smartphones and advanced defense systems. The move has sparked widespread concern across industries and governments alike, as it threatens to disrupt supply chains, drive up costs, and accelerate the search for alternative sources and technologies. In India, the ripple effects are being felt acutely, prompting urgent discussions and strategic responses from policymakers, manufacturers, and investors.

China's decision in April 2025 to impose export restrictions on seven Rare earth elements and associated magnets represents a significant disruption to global supply chains with particular implications for India's growing technology and manufacturing sectors. This strategic move, widely viewed as Beijing's response to heightened U.S. tariffs, has exposed critical vulnerabilities in the global supply chain for these essential materials that power everything from electric vehicles to wind turbines and defense technologies.

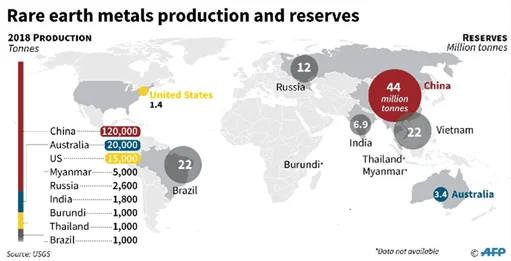

China currently controls approximately 60% of global rare earth processing capabilities and supplies around 90% of the world's rare earth magnets, despite holding only 38% of global reserves. This concentration creates exceptional leverage, which China appears increasingly willing to deploy for geopolitical advantage. The restrictions specifically target terbium, yttrium, dysprosium, gadolinium, lutetium, samarium, and scandium. These elements are critical for high-performance magnets used in green technologies and advanced electronics.

For India, this development creates both significant risks and potential opportunities. High-risk exposure is concentrated in sectors dependent on rare earth magnets, particularly companies accelerating their EV production plans. The Indian auto industry has already begun seeking government intervention to expedite Chinese approvals for rare earth magnet imports, signaling immediate supply chain concerns. With India's rare earth magnet market valued at USD 637.4 million in 2024 and projected to reach USD 993.0 million by 2033, the stakes for domestic industry are substantial.

Rare Earth Magnets 101

What Are Rare Earth Elements?

Rare Earth Elements (REEs) are a group of seventeen elements, comprising the fifteen lanthanides on the periodic table along with scandium and yttrium. Despite their name, most rare earths are relatively abundant in the Earth's crust but rarely found in concentrated, economically viable deposits. These elements are typically classified into two categories:

Light Rare Earth Elements (LREEs): Those with atomic numbers from 57 to 63, including lanthanum (La), cerium (Ce), praseodymium (Pr), neodymium (Nd), promethium (Pm), samarium (Sm), and europium (Eu).

Heavy Rare Earth Elements (HREEs): Those with atomic numbers from 64 to 71, including gadolinium (Gd), terbium (Tb), dysprosium (Dy), holmium (Ho), erbium (Er), thulium (Tm), ytterbium (Yb), and lutetium (Lu). Scandium and yttrium are also grouped with HREEs due to similar chemical properties.

REEs are characterized by high density, high melting points, high conductivity, and high thermal conductance. Their unique electronic structures, particularly the presence of unpaired electrons, make them exceptionally valuable for creating powerful magnetic fields.

LREE vs. HREE: Where India Lacks

In India, LREEs such as neodymium and praseodymium are abundant and primarily found in monazite-rich beach sands along the eastern and southern coasts.

India has established extraction and refining capabilities for LREEs up to the oxide and carbonate stage, but industrial-scale conversion to magnets is still limited, with most output used in basic compounds or exported.

LREEs are mainly used in bulk applications like automotive (EVs), electronics, glass, and catalysts. While extraction is technologically feasible, it remains complex due to low grades, radioactivity, and environmental regulations.

The main challenge is scaling up downstream value addition, particularly in magnet manufacturing.

HREEs such as dysprosium and terbium, in contrast, are extremely scarce in Indian deposits and not available in extractable quantities.

India lacks both the resource base and the technology for HREE extraction and processing, making the country entirely dependent on imports (mostly from China) for these critical materials.

HREEs are vital for high-performance magnets used in defense, wind turbines, and advanced electronics, making them highly strategic and critical for India’s energy transition and national security.

The absence of domestic supply and processing capacity for HREEs exposes India to significant supply chain risks, especially amid global disruptions or export restrictions.

Thus, while LREEs represent an area of strength and opportunity for India, HREEs remain a major vulnerability, underscoring the need for international partnerships, recycling, and policy reforms to enhance supply security and downstream capabilities.

What Are Rare Earth Magnets?

Rare earth magnets are exceptionally strong permanent magnets made from alloys of rare earth elements, primarily neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) and samarium-cobalt (SmCo). They are much stronger than conventional magnets like ferrite or alnico, allowing for smaller, lighter components in advanced technologies.

These magnets are indispensable in a wide range of applications: EV motors, wind turbine generators, computer hard drives, speakers, headphones, MRI scanners, industrial automation, and defense equipment. Their unique strength and compactness make them critical for miniaturized and high-performance devices.

Supply Chain Concentration & Geopolitical Dynamics

China's Dominance in the Rare Earth Value Chain

China's control over the global rare earth supply chain represents one of the most significant resource concentrations in the modern industrial economy. This dominance extends across the entire value chain, from mining to processing to magnet manufacturing:

Mining: As of 2024, China produces more than two-thirds of the total global rare earth mine production, with the United States a distant second at 11.6% market share.

Processing: China controls approximately 60% of global rare earths processing capabilities, compared to the United States at 15% and Australia at 8%.

Magnet Manufacturing: China supplies approximately 90% of the world's rare earth magnets, creating a near-monopoly on these critical components.

This dominant position did not occur by accident. Beginning in the 1990s, Beijing classified rare earths as strategic resources, shielding the sector from foreign control and channeling significant state support into extraction and refining. As Western nations shut down domestic operations over cost and environmental concerns, China ramped up investment, perfecting processing techniques initially developed in the United States.

By the early 2000s, China produced up to 97% of the world's rare earths and began restricting exports, simultaneously driving up global prices and encouraging foreign manufacturers to relocate operations to China to secure uninterrupted supply.

In April 2025, China extended export restrictions to seven key rare earth elements: terbium, yttrium, dysprosium, gadolinium, lutetium, samarium, and scandium, as well as magnets produced from these materials. The move requires companies to secure special export licenses rather than implementing an outright ban.

This action appears directly linked to geopolitical tensions, specifically described as a response to U.S. President Donald Trump's tariff increases on Chinese products. The timing aligns with broader strategic competition between the United States and China, particularly in high-technology sectors.

The restriction targets elements with critical applications:

Terbium: Vital for smartphone displays and aircraft magnets

Yttrium: Used in medical lasers and superconductors

Dysprosium: Key for EV magnets and wind turbines

Gadolinium: Common in MRI scans and reactor cores

Lutetium: Used in oil refining

Samarium: Strategic for military-grade magnets

Scandium: Critical for aerospace applications

Where does India Stand?

Current Domestic Production Capabilities

India possesses significant rare earth element resources but has developed only limited processing capacity and virtually no high-volume magnet manufacturing capability. India has a large rare earth reserve, enough to last around 450 years according to some sources, but most of them are concentrated around LREEs.

The country's rare earth operations are primarily controlled by IREL Limited, a public sector undertaking under the Department of Atomic Energy.

IREL's production facilities include:

Rare Earths Division at Aluva, Kerala: Established in 1952, this facility processes monazite and produces high-purity rare earth compounds including lanthanum, cerium, neodymium-praseodymium, samarium, gadolinium, and yttrium oxides.

Odisha Sand Complex (OSCOM) and Rare Earth Extraction Plant (REEP) at Chhatrapur, Odisha: IREL's largest division, processing 10,000 tonnes per annum of monazite to produce rare earth chloride and other compounds.

Rare Earth Permanent Magnet Plant at Visakhapatnam: Opened in 2023, this facility produces samarium-cobalt permanent magnets using indigenous technology. The plant has an annual capacity of just 3,000 kg with an overall investment of 197 crore rupees.

India has substantial beach sand mineral deposits containing monazite (a source of rare earths) across coastal regions in Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Gujarat. The country has installed capacity to process about 10,000 MT of rare earth-bearing minerals.

However, India's domestic production has significant limitations:

Focus primarily on mining and initial processing rather than high-value downstream products

Limited capacity for producing finished magnets (only 3 tonnes annually of SmCo magnets)

Production skewed toward light rare earths, with heavy rare earths (like dysprosium and terbium) in short supply

No commercial-scale production of neodymium magnets

Mineral Availability vs. Processing Capability

India faces a situation common to many countries i.e. possessing raw materials but lacking advanced processing capabilities. According to government sources, "Some REE which are available in India such as Lanthanum, Cerium, Neodymium, Praseodymium, Samarium, etc. are in supply surplus while Dysprosium, Terbium, Europium which are classified as HREE are having supply constraint. These HREEs are not available in Indian deposits in extractable quantity".

This creates a structural imbalance where India must import the highest-value rare earths and finished magnets despite having domestic resources for some elements. The critical bottleneck is not mining capacity but the sophisticated processing technology and know-how required to convert rare earth oxides into metals and then into high-performance magnets.

China's decades-long investment in refining technology and relatively lax environmental regulations have been key drivers in establishing and maintaining its control over these critical processing steps.

What are Indian Industries saying?

Automobile Industry:

India’s automobile sector is facing a severe crisis due to China’s recent export restrictions on rare earth magnets, which are critical components for EVs, hybrids, and certain internal combustion engine vehicle systems.

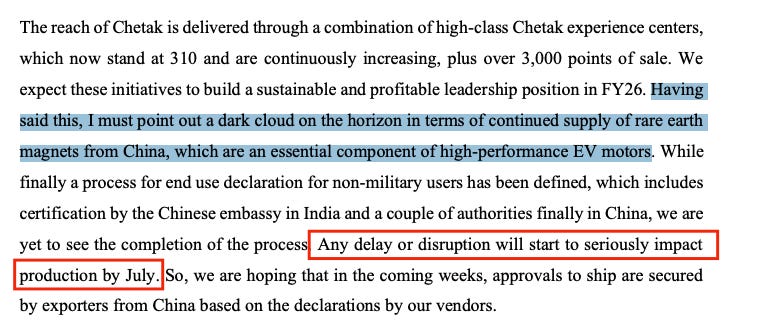

The impact is immediate and acute for Indian automakers, especially as the sector prepares for a wave of new EV launches, most of which rely on permanent magnet synchronous motors (PMSMs) that use these rare earth magnets for high torque and efficiency. Major manufacturers like Maruti Suzuki have already slashed near-term EV production targets. Maruti Suzuki has cut e-Vitara output by two-thirds and while Bajaj Auto and others warn of possible production halts by July if the situation persists.

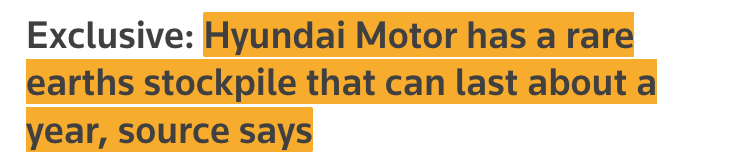

Most automakers currently have just 4–6 weeks of magnet inventory; if supply disruptions last beyond a month, production of both EVs and ICE vehicles could be significantly affected, with potential deferrals or rescheduling of new model launches starting as early as July 2025. Notably, amongst all this crisis, Hyundai has confirmed that they have rare earth magnet stockpile of about a year and don’t see any major disruptions in the notable future.

Other players like Delta Autocorp who are manufacturers and sellers of 2W and 3W EVs have mentioned that they have the option of sourcing the entire motor from China, instead of importing the magnets and manufacturing the motor here in India.

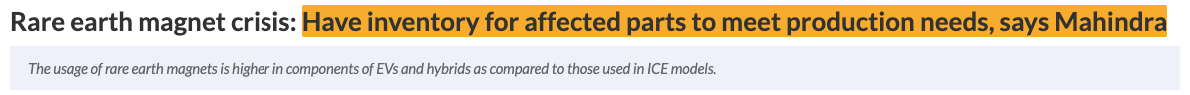

Mahindra & Mahindra also issued a statement saying that they have enough rare earth magnets to meet their immediate production needs:

In response, the Indian auto industry is lobbying the government to expedite Chinese approvals and seeking alternative suppliers in countries like Vietnam, Indonesia, Japan, Australia, and the US. Short-term mitigation measures include building strategic inventories and optimizing existing stocks, while long-term strategies focus on developing domestic rare earth processing, magnet manufacturing, and recycling infrastructure. However, given the overwhelming dependence on Chinese supply and the lack of immediate alternatives, the rare earth magnet crisis has emerged as a major supply-side threat, risking a repeat of the semiconductor shortage’s disruptive impact on the Indian automotive sector

Other Industries

In the past two months, Indian companies outside the automobile sector have not issued many public commentaries specifically addressing the rare earth magnet crisis. However, several industry-wide and sectoral concerns have surfaced, especially from defense, energy, and medical equipment manufacturers.

Government Initiatives and Policy Framework

India's government has recognized the strategic importance of rare earth elements and has implemented several initiatives to strengthen domestic capabilities:

Department of Atomic Energy Oversight: Rare earth mining and processing in India are regulated through the DAE, reflecting their strategic importance.

Capacity Building for LREE Consumption: The government is "actively engaged in capacity building for consumption" of light rare earth elements that are available domestically in surplus.

Visakhapatnam Magnet Facility: The establishment of the samarium-cobalt magnet production facility at Visakhapatnam represents a small but significant step toward domestic magnet manufacturing.

PLI Schemes: While not specifically targeting rare earths, various PLI schemes support industries that could benefit from domestic rare earth processing and magnet manufacturing.

However, India's policy approach has notable limitations:

Focus on mining rather than high-value processing and manufacturing.

Regulatory constraints that limit private sector participation.

Insufficient investment in R&D for alternative materials or processing techniques.

Absence of a comprehensive national strategy comparable to those implemented by Japan or the European Union.

Setting up of KABIL:

The KABIL Project, or Khanij Bidesh India Limited, is a joint venture established in August 2019 by three Indian government enterprises: National Aluminium Company Ltd., Hindustan Copper Ltd., and Mineral Exploration & Consultancy Ltd., under the Ministry of Mines. Its primary mandate is to ensure a steady and secure supply of critical and strategic minerals such as lithium, cobalt, and other minerals essential for batteries, electric vehicles, defense, and renewable energy which are either scarce or unavailable in India.

KABIL’s strategy focuses on identifying, acquiring, developing, and mining critical mineral assets overseas, particularly in countries rich in such resources. The company is actively pursuing lithium and cobalt projects in Argentina, Australia, and Chile, including exclusive exploration rights in Argentina’s Catamarca Province and partnerships with government agencies in Australia and Chile. KABIL also collaborates with Indian research institutions like CSIR-IMMT to enhance its mineral processing and technological capabilities.

Does this Chinese Export Restrictions have a precedence?

This is not the first time China has wielded rare earths as a geopolitical tool. On September 7, 2010, following the arrest of a Chinese fishing boat captain by the Japanese coastguard near the disputed Senkaku Islands, China halted rare earth exports to Japan. At the time, Japan depended on China for nearly 90% of its rare earth imports, and the embargo sent Japanese industry, particularly the automotive sector, into panic.

The crisis resolved when Japan released the fishing boat captain, but rare earth prices soared tenfold in the year following the incident. This event served as a wake-up call for Japan, which subsequently implemented a comprehensive strategy to reduce dependence on Chinese rare earths, including:

Developing technologies to reduce rare earth usage

Researching alternative materials

Promoting recycling

Developing mines in Australia and elsewhere

Establishing strategic stockpiles

These efforts proved partially successful, reducing Japan's dependence on Chinese rare earths from 90% to 60% and cutting the country's rare earth consumption by half.

Japan is still very much dependent on China for their rare earth mineral consumption, however the crucial thing here to understand is the promotion of recycling of rare earths which will be important for India as well.

Are their any companies in India focusing on Rare Earths recycling?

Yes, several companies and initiatives in India are now focusing on rare earths recycling, but for the sake of this article, let’s focus on the listed players only:

Namo eWaste Management Ltd.:

Namo eWaste Management Limited operates a 10,000 metric ton e-waste plant in Nasik and has recently expanded to include a lithium-ion battery recycling facility. Their recycling process has two main streams: about 20–30% of batteries are refurbished if some cells still have usable life, while the remaining 70% are shredded to produce "black mass" which contains lithium, cobalt, and rare earth metals. The company does not currently refine these metals from the black mass due to the extremely high capital expenditure required which is over half a billion dollars globally for such operations.

Instead, Namo focuses on producing high-quality black mass, which it exports to leading global refineries, mainly in China and Taiwan. The company notes that while there are some solutions for further processing in India, these are not efficient or scalable enough for industrial-level extraction of rare earths. As a result, exporting to top international players remains their primary strategy until domestic refining capabilities improve.

Owais Metals and Minerals Processing Ltd.:

Owais Metal & Mineral Processing Limited has commenced commercial production of high-purity Tantalum Pentoxide, Niobium Pentoxide, Titanium Dioxide, and Tin, positioning itself as a pioneering Indian company recovering these strategic minerals from mining waste. The company has announced development of its proprietary technology for extracting such "rare elements" from residual slag, supporting India’s self-reliance vision. Their advanced processes enable the transformation of mining waste into valuable inputs for capacitors, semiconductors, and high-tech industries, with plans to further expand production capacity and become a leading recycler specializing in the recovery of rare minerals from waste streams.

What Listed Mining Companies are working in Rare Earth Magnets?

Gujarat Mineral Development Corporation (GMDC):

GMDC is positioned to be a major beneficiary of the current rare earth crisis triggered by China’s export restrictions and global supply disruptions. As one of India’s leading mining and mineral processing companies, GMDC is developing the Ambadongar rare earth deposit in Gujarat, one of the world’s largest known sources REEs. The company has unveiled a comprehensive plan to establish a full rare earth supply chain: from mining and beneficiation to processing and even downstream manufacturing of magnets and batteries and thereby aiming to make Gujarat a global REE processing hub.

With ₹2,200 crore investment earmarked for mining and processing and an additional ₹1,300 crore for a state-of-the-art processing hub, GMDC targets annual production of 12,000 tonnes of rare earth oxides by FY28, which could meet up to 15% of India’s demand for neodymium and praseodymium. This has led to strong investor interest, with GMDC’s stock rallying significantly in recent weeks as the market recognizes its potential to fill the rare earth supply gap and capitalize on high prices and demand. In summary, GMDC stands to gain both financially and strategically as India accelerates efforts to secure its own rare earth resources and value chain in response to global shortages.

Permanent Magnets Ltd.

PML recently has reaffirmed its long-term plan to establish a full rare earth magnet supply chain within India. The company’s approach is to first set up application and assembly operations, with backward integration into magnet manufacturing as the next phase. Management emphasized that while the near-term outlook is uncertain, their strategic goal remains to localize rare earth magnet production to meet the anticipated surge in domestic demand from EVs and other applications by 2030. PML is also exploring alternative partners and technology sources outside China to mitigate geopolitical risks and is planning pilot facilities as a precursor to larger-scale investments. The company remains committed to expanding its capabilities and believes that, despite temporary setbacks, these initiatives will position it as a key player in India’s rare earth magnet value chain as the market evolves.

Moving Away from Rare Earth Magnets:

Developing mining and processing capabilities will take billions of dollars of Capex and upto a decade to see any meaningful results. Meanwhile, developing technologies that don’t use rare earth magnets is also a viable alternative. There are some listed Indian companies that are precisely trying to achieve that:

Sterling Tools Ltd.

Sterling Tools, through its subsidiary Sterling Gtake E-Mobility (SGEM), is entering the manufacturing and marketing of rare earth magnet-free traction motors for electric vehicles in India. The company has signed a technology licensing agreement with UK-based Advanced Electric Machines (AEM) Ltd, enabling it to produce high-performance motors that do not require rare earth magnets, thus providing a direct alternative to conventional permanent magnet motors, which are heavily dependent on Chinese supply chains.

This initiative is strategically timed in response to recent Chinese export restrictions on rare earth elements and magnets, which have disrupted global supply and highlighted the risks of over-reliance on imports. The company explained that the new REM-free motors do not use any permanent magnets, thus eliminating dependence on rare earths and insulating the supply chain from geopolitical risks and cost spikes. The Bill of Materials (BOM) cost for these motors is expected to be similar to, or even lower than, that of traditional magnet-based motors, especially as rare earth prices rise. Sterling Tools believes this technology will slowly gain acceptance, particularly as OEMs seek alternatives to mitigate supply chain risks.

Customer trials and validation for these REM-free motors are set to begin immediately, with commercial production targeted for the next fiscal year. Management expects the customer validation process to take about 6 months, with full production scaling up over the following year. Management emphasized that while initial market penetration may be modest, the long-term potential is significant, especially if rare earth supply remains constrained. The company is investing in R&D, expanding its tech center, and building a comprehensive power electronics and magnetics capability to support future growth in the EV segment.

Sona BLW Precision Forgings Ltd.

In the latest earnings call, Sona BLW Precision Forgings Ltd (Sona Comstar) confirmed that constraints on rare earth supplies that are exacerbated by recent geopolitical developments. This has prompted the company to accelerate its development of magnetless (rare earth-free) motors. CEO Vivek Vikram Singh stated that while the technology for magnetless motors is sound, achieving the required efficiency has been a challenge, but ongoing work is focused on overcoming this. He also noted that Sona Comstar had already developed non-rare earth motors as early as 2021, and these are technically ready for production, though they are heavier and require customer acceptance before widespread adoption.

Singh emphasized that the current rare earth supply crisis is a wake-up call for the industry, highlighting the risks of overdependence on any single source or material that can be used as a geopolitical negotiating tool. He suggested that customer urgency for rare earth-free solutions may increase given the current situation, and reiterated the strategic importance of developing alternatives to ensure supply chain resilience and reduce vulnerability to global disruptions.

In conclusion, the rare earth magnet crisis triggered by China’s export restrictions has exposed critical vulnerabilities in India’s supply chain, impacting key sectors such as electric vehicles, renewable energy, and defense. Indian companies like Sterling Tools and Sona Comstar are proactively responding by accelerating the development of rare earth magnet-free motor technologies, aiming to reduce dependence on scarce and geopolitically sensitive materials. Meanwhile, firms such as Owais Metal & Mineral Processing Limited and Gujarat Mineral Development Corporation are expanding domestic capabilities to recover and process critical minerals from mining waste and indigenous deposits, supporting India’s vision of self-reliance (Aatma Nirbhar Bharat). Recycling initiatives led by companies like Eco Recycling, alongside government-backed incentives, further bolster efforts to build a circular economy for critical minerals. Collectively, these strategic moves underscore a growing recognition that diversifying supply sources, investing in alternative technologies, and strengthening domestic production are essential to safeguarding India’s industrial growth and national security in an increasingly uncertain global landscape.